by Ronald Sklar

Copyright ©2005

PopEntertainment.com.

All rights reserved.

If

imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, then Grant Wood must be

flattered out the wazoo. Although the artist of “American Gothic” died in

1942, his painting has gone on to symbolize all things American, and

parodied by Madison Avenue, Hollywood, and both the left and right-wing

press.

This odd depiction of our culture has inspired, flabbergasted, outraged

and obsessed generations of Americans. However, everybody instantly

recognizes it and somehow “gets” it.

Arguably the most famous painting in our country’s history (“Whistler’s

Mother” is a distant second), the work was almost rejected and forgotten

when it was first presented in 1930. It has since developed a legendary

story about the ultimate in recycling.

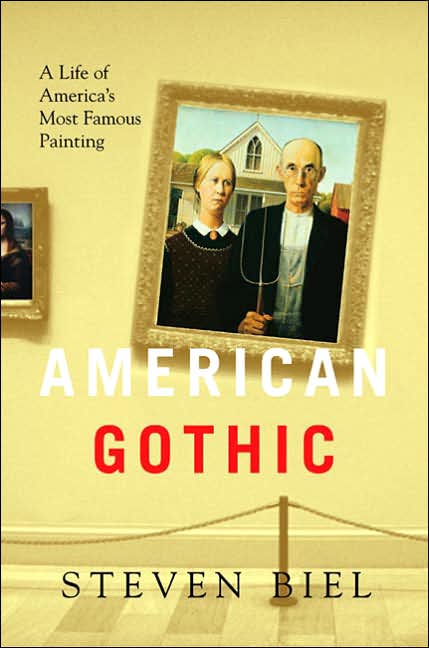

This fascinating chapter in American history has been captured by Harvard

historian Steven Biel in his new book, American Gothic: A Life

of America’s Most Famous Painting (W.W. Norton and Company). Here, he

takes a few moments to reveal the painting’s importance.

What inspired you to

write this book?

I’m

interested in objects and events that have become overly familiar. I wrote

a book about the Titanic disaster a few years ago (Down with the Old

Canoe). This was before the [1997] movie came out, before it saturated

popular culture more than ever. I’m interested in things that have been

flattened out to clichés and I try to recover the history behind them and

find out why they’re famous. In this case, [the painting’s fame] is all

out of proportion to its humble origins and to its artistic merit compared

to other "masterpieces.”

What is the story

behind the painting?

Grant Wood was an unknown artist from Cedar Rapids,

Iowa in 1930. He went down to a small town in south-central Iowa

called Eldon. He traveled there because a friend of his was running a

community fine-arts project. He was riding around in a car with another

artist named John Sharp. While riding, they encountered this house on the

outskirts of Eldon – an extremely modest clapboard house, but it had this

gothic window, which stood out. It was not completely

unexceptional in the Midwest, but it was strange enough to get Wood to get

out of the car.

He

decided to put some figures in the foreground that could possibly belong

to this strange house. He had his sister and his dentist pose for it. He

distorted them – he elongated them with grim expressions. Then he entered

it into a contest at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it received third

prize. A notable critic reprinted it in newspapers, and from there, it

took off.

Originally, it took off because it was ridiculing the Midwest and the

kinds of people who supposedly lived there

– uptight, repressed, puritanical and generally

nasty. The sort of yokels that writers like H.L. Mencken would poke fun at

throughout the 1920s. It also stirred up a controversy in Iowa because the

farmers really thought it was an insult to them. Its initial fame was born

out of controversy, out of the perception that its meaning was satirical.

Describe the painting

strictly from an artistic and aesthetic viewpoint.

It’s a realistic portrait of a man and a woman posed in front of a house.

The woman is wearing a rickrack apron. The man is wearing overalls, a dark

coat and a collarless shirt. He’s holding a hayfork, which directly

mirrors the gothic window. The pattern of the hayfork is repeated in the

pattern of the man’s overalls if you look closely. There is a

clear

blue sky in the background, highly stylized, rounded trees, a red barn

off on the right side, a snake plant on the porch on the left that mirrors

a lock of hair running down the woman’s neck. The man is directly looking

at the viewer. The woman is looking off to the side.

Some have said that what lends itself to parody formally

is that you have these two figures facing us

and it’s easy to plug other faces into them

and to substitute something else in place of the pitchfork.

In the beginning, the painting was despised by certain people and

celebrated by others. As time went on, the painting took on new meanings.

It

was despised and embraced, as far as I can tell, for the same reasons. It

was perceived as being a work of satire. The critics who really made

Wood’s reputation understood it that way. They understood him as a victim

of these people and their repressiveness and hostility.

Initially, the people who despised it were Iowa farmwives who wrote

letters to newspapers protesting being depicted as primitive idiots.

How exactly did this painting become an American icon, the most famous

painting in American history?

There is no quantifying that, really, but I would say so. It happened

because over the course of the thirties in the context of the depression

and throughout World War II, it changed from being that satirical image to

a national symbol of stability, order, prosperity, virtue and

wholesomeness.

Instead of holding its subjects up to ridicule, it now came to be seen as

holding them up for admiration as quintessential Americans. In hard

times, the “let’s make fun of yokels” idea seemed kind of cruel. The

conservative virtues of the Midwest were re-embraced by some East Coast

critics, and even the left in the 1930s paid homage to the fortitude of

the “folk.” It was a way of fighting off despair.

Some people say that the subjects are husband and wife; others say they

are father and daughter. Which is it?

Wood was non-committal on this. His sister, Nan, probably because she was thirty-something when she posed

[and Dr. McKeeby was in his sixties], was really offended by the idea that

they might be husband and wife. It was she who really took the lead in

insisting that they w ere meant to be father and daughter. Wood, as far as we

know, left no record of his intentions. We don’t have anything that tells

us what he was thinking when he painted this.

ere meant to be father and daughter. Wood, as far as we

know, left no record of his intentions. We don’t have anything that tells

us what he was thinking when he painted this.

Everything

that he says about this comes after the fact, and it comes from responding

to those people who hated it. He said that he didn’t mean to make fun of

anybody and that he was a loyal son of the Midwest. Strangely enough, he said sometimes that they were

father and daughter and as time went on he seemed completely comfortable

in saying that they were a couple. He went back and forth and didn’t seem

to have a particular stake in it one way or the other.

The

fact that it is ambiguous has opened the door to these gothic

interpretations of the painting: what is the relationship between these

two people? What is going on behind that curtain? What kind of creepy

things might be happening in that house?

Wood’s sexuality was rather ambiguous. Do you think that influenced the

painting in any way?

If

I don’t have solid evidence on this, then I’m not really willing to go

there. Circumstantially, yes, he lived with his mother until he was into

middle age. He married very late. It was a terrible marriage by every

account. It rather quickly ended in divorce. Speculations about his

sexuality aren’t entirely unreasonable, but suggesting that it would have

certain aesthetic consequences

simplifies the relationship between sexuality and

artistic production. [For example,] the critic Robert Hughes suggested

that this is some kind of gentle satire because Wood was a closeted

homosexual. To me, it doesn’t illuminate that much.

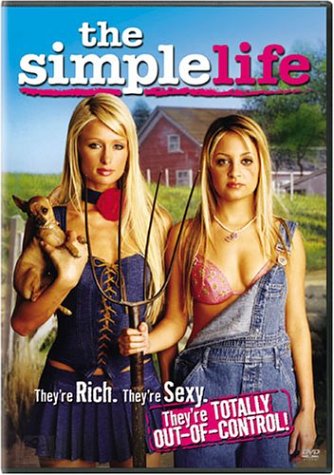

From the sixties

onward, this painting becomes a real source of parody -- everything from

Green

Acres to

the yuppies to

The Simple Life.

I

started thinking about where I first became aware of this image. It

certainly wasn’t at the Art Institute of Chicago and I certainly didn’t

see it in a non-parodied form first. The first time I became aware of it

was in a Country Corn Flakes commercial and in the opening credits of Green Acres. It had already become such a well-known image that it

was

an easy move to make. If you want to send up American heartland values or

if you want to encapsulate those values in a single image, you use

“American Gothic.” It’s a really effective shorthand way of capturing

those myths of the true America.

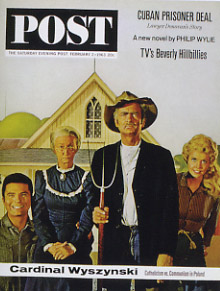

The Beverly Hillbillies

on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post [in 1963] is suggesting

something about the wholesomeness of these yokels who find themselves in

the corruption of LA. In an issue of TV Guide in the late sixties,

Irene Ryan [who played Granny] really defends the non-ironic

interpretation of “American Gothic.” Ryan said that the timeless values of

“American Gothic” are the antidote to what was going on in the late

sixties. She really identified with that image.

After that, the floodgates just opened. The first presidential couple to

be parodied was the Johnsons. Every presidential couple since then have

been plugged into the “American Gothic” pose.

Then you start to get these lifestyle parodies, where those old-fashioned

people in the painting aren’t having any

fun, but we are, with a tennis racquet or an electronics product instead

of a pitchfork. They are playing on the immediate recognition of the image and at the same

time saying that consuming this or that product is wholeheartedly

American.

The

joke couldn’t be more blatant than with Paris Hilton and Nicole Ritchie in

The Simple Life. These people are being plopped into middle America

and there is a clash of values. That’s the whole premise of the show.

Is the actual

painting itself still relevant today?

It’s

hard for a parody of this painting to really work anymore, to carry any

kind of potent message. To give it some power, to make it stand out from

all the other parodies, takes extraordinary creativity. Of course, it’s

impossible for it to stir up the passions that it stirred up in 1930. But

it’s well worth understanding its rich history and coming to see how and

why, at one time, it had the power to offend people.